- 1Department of Geosciences, Boise State University, Boise, ID, United States

- 2Department of Geological Sciences, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA, United States

Individuals with physical disabilities are largely underrepresented in the geoscience workforce. In this study, we analyzed over 2,500 job advertisements (ads) for entry-level geoscience positions across 19 industries to assess how inclusive the United States job market is for people with physical disabilities. We evaluated each ad’s Equal Opportunity Employer (EEO) and accommodation statements to create a measure of geoscience employers’ inclusive practices for people with disabilities. We coded each ad for instances where physical abilities (e.g., traversing rough terrain, driving a vehicle, lifting heavy objects) were listed as required or preferred qualifications and whether these abilities matched the core job function. A significant proportion of job ads (44%) did not include EEO statements, and of those that did, the language used was minimal or abbreviated. Additionally, only 18% of ads mentioned accommodations for people with disabilities. Of the ads that required physical abilities, only 19% requested physical abilities that matched the core job function. Students exploring their career options or applying for entry-level jobs may feel disadvantaged, restrict their applications, or dismiss geoscience careers if they have physical limitations, or if they perceive that the work environment is not inclusive. Overall, online geoscience ads could benefit from adding or modifying equal opportunity employment and accommodations statements to reflect a more inclusive workplace and could explicitly link requested physical abilities to the job description. These results could help employers consider possible modifications to their job advertisements and explore alternative strategies to promote a more inclusive geoscience workforce.

Introduction

Individuals with disabilities are the largest underrepresented group in the United State (U.S.) workforce. People with disabilities are disproportionally unemployed, underemployed, or absent from the labor force, despite actively seeking employment (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). The most recent demographic data indicate that approximately 61 million adults in the United States, or about 1 in 4, have some form of disability (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Of those, 1 in 7 have a physical disability that limits their mobility. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2022, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities was 7.6%, compared to 3.5% for people without disabilities. In the geosciences, these statistics are even more alarming as less than 10% of the current geoscience workforce is comprised of individuals with a disability (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2023).

The geoscience field suffers from a stereotype that geoscience careers are for able-bodied individuals (Atchison and Libarkin, 2016). A Google search on “geoscientists” yields images of scientists working in remote, rugged field locations. In reality, however, many geoscience careers are lab-based, computer-based (Shafer et al., 2023), or use techniques to acquire data that do not require physical mobility (Karpatne et al., 2018), much less extended field campaigns. The common perception that the geoscience workforce is only for the able-bodied may lead qualified people with disabilities to search for careers elsewhere. Additionally, research shows that stigma and stereotyping by employers can lead to negative attitudes towards people with disabilities and can prevent them from being considered for job opportunities (Hampson et al., 2020). Discrimination in the workplace can take many forms, such as not providing reasonable accommodations and passing over candidates qualified for promotion (Robert and Harlan, 2006). People with physical disabilities may be hesitant to disclose their disability to their employer due to fear of negative repercussions, such as being denied job opportunities or being treated unfairly in the workplace (Von Schrader et al., 2014). Addressing these barriers will require not only changes in employer attitudes and practices but also increased support for individuals with physical disabilities in the geoscience community as a whole.

Job advertisements (ads) often serve as the first communication between employers and prospective job applicants. These ads are the employer’s opportunity to convey important information about the open position, including the job title, responsibilities, and qualifications. Ads can also provide a sense of a company’s culture, values, and work environment. For job seekers, ads convey the types of employees that are being sought and can help applicants determine if the position aligns with their skills, experience, and career goals (Harper, 2012). Language in ads, such as statements about a company’s commitments to creating a diverse and inclusive workforce, signals to applicants how welcome they are within the company on the basis of their identity. A lack of inclusive language may deter a person with physical disabilities from applying.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a U.S. federal law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in employment, public accommodations, transportation, telecommunications, and state and local government services. Title I of the ADA requires that employers make their job application processes accessible or provide reasonable accommodations for persons with disabilities to apply for jobs, unless employers can show that doing so would cause them undue hardship (Americans with Disabilities Act, 1990). However, the ADA does not require employers to provide statements explaining available accommodations in their ads and companies may place accommodation statements in ads on their own accord. Similar to accommodation statements, equal opportunity employer (EOE) statements demonstrate that an organization agrees not to discriminate against any employee or job applicant because of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, physical or mental disability, or age. As with accommodation statements, EOE statements in job advertisements are also not required by law. However, ads created by the federal government or contractors associated with the federal government are required by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to have EOE statements (United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1992). Although these steps taken by the ADA and EEOC are aimed at safeguarding the rights of people with disabilities in the workforce, people with disabilities continue to face substantial employment inequalities (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023).

Geoscientists address many societally relevant problems, and only through diverse perspectives, representative of everyone affected, can we adequately analyze complex problems. Considering that people with disabilities represent such a large portion of the population, their participation in the geoscience workforce is essential. In this study, we examine geoscience job advertisements to characterize initial barriers people with disabilities may face when entering the U.S. geoscience workforce. We ask: how inclusive are geoscience job advertisements to applicants with disabilities transitioning to the workforce?

Methods

From May to November, 2021 and 2022, we collected 2518 U.S.-based job ads from four online search engines: Indeed.com, USAJobs.gov, careerbuilder.com, and collegerecruiter.com. All ads required or preferred a geoscience-related bachelor’s degree and were concentrated on entry level positions (i.e., jobs requiring little to no experience). We assigned each ad an occupation as defined by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2018 Standard Occupational Classification Systems (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018) and an industry sector as defined by the 2018 American Geosciences Institute (AGI) Status of the Geoscience Workforce Report (Wilson, 2019). Additional details about the collection and classification of the job advertisements are described by Shafer et al. (2023). When making comparisons among ads for different occupations, we only include occupations with >50 advertisements.

We conducted a content analysis of each ad’s Equal Opportunity Employer (EOE) and accommodation statements to create a measure of geoscience employers’ inclusion of people with disabilities. We developed two criteria, one for categorizing employer EOE and another for categorizing accommodation statements using a subset of the ads (n = 40), and iteratively refined the categories through further analysis (Tables 1, 2). Additionally, we recorded where in the ad the EOE and accommodation statements were placed (e.g., at the bottom of the ad or next to the listed physical abilities), as well as statement formatting (e.g., paragraph or bullet points). We assume that the most important information is listed first where the reader is likely to see it or where it is most applicable. In the case of accommodation statements, listing the statement next to the requested physical ability might be more noticeable to applicants with physical disabilities.

The four online job search engines do not have a limit on the amount of content an employer can post in a single advertisement. However, each website provided word limit suggestions to optimize the number of applications. For example, Indeed.com states “Job postings with descriptions between 700 and 2000 characters get up to 30% more applicants than other job postings.” (Indeed, 2023) The price for Indeed.com, careerbuilder.com, and collegerecruiter.com advertisements is dependent on how many applicants apply for each job posting (Indeed, 2023). There is no price for USAJobs.gov ads because all federal agencies are required to advertise positions through that website.

Many geoscience employers request the applicant be able to perform some physical action as part of their job duties (e.g., traversing rough terrain, driving a vehicle). We created a third criterion to categorize how well a requested physical ability matched the core job description (Table 3). We used the case-insensitive, code-matching model and search criteria employed by Shafer et al. (2023) to identify which ads from the set of 2,518 requested physical abilities. Our initial analysis indicated that driving was the most commonly requested physical ability. Therefore, we occasionally report driving and non-driving physical abilities separately throughout. Because EOE and accommodation statements vary greatly by employer, and because the subjective approach we took to determine if a requested physical ability was critical for the core job function, we imported the 2,518 ads into NVivo for manual coding according to the criteria described in Tables 1–3. All manual coding of the ads was completed by the lead author. The coder used the criteria in Tables 1–3, which were developed by all three authors, to code the ads. We compared the number of ads that requested a physical ability and whether or not the ad included an accommodation statement.

The results of our study should be used and considered with the following limitations. First, this study addresses employment barriers in job advertisements only for individuals with a physical disability. We reviewed text in job advertisements specifically looking for employer requests for physical abilities and for accommodation statements that address the physical nature of some geoscience jobs. We acknowledge that barriers to employment exist for people with non-physical disabilities but those were not addressed in this study. Secondly, we can only take job advertisements at face value and are limited by the information employers choose to provide in their ads. It is possible that employers choose to promote their inclusive practices on their company website rather than in their job advertisements, or that for other reasons the ads do not reflect the employer’s values. Finally, the aim of this work is to document the use of inclusive language in job advertisements with the hope that geoscience employers reflect on and modify their advertising practices. We did not investigate the perceptions that individuals with disabilities have of this language. We acknowledge that highlighting the voices of individuals with physical disabilities and their lived experiences when navigating the geoscience job market is also critical to improving the diversity and inclusivity of the workforce (Kingsbury et al., 2020). Our results documenting the language used in geoscience job advertisements could serve as a starting point for such work.

Results

Job Ad Characteristics

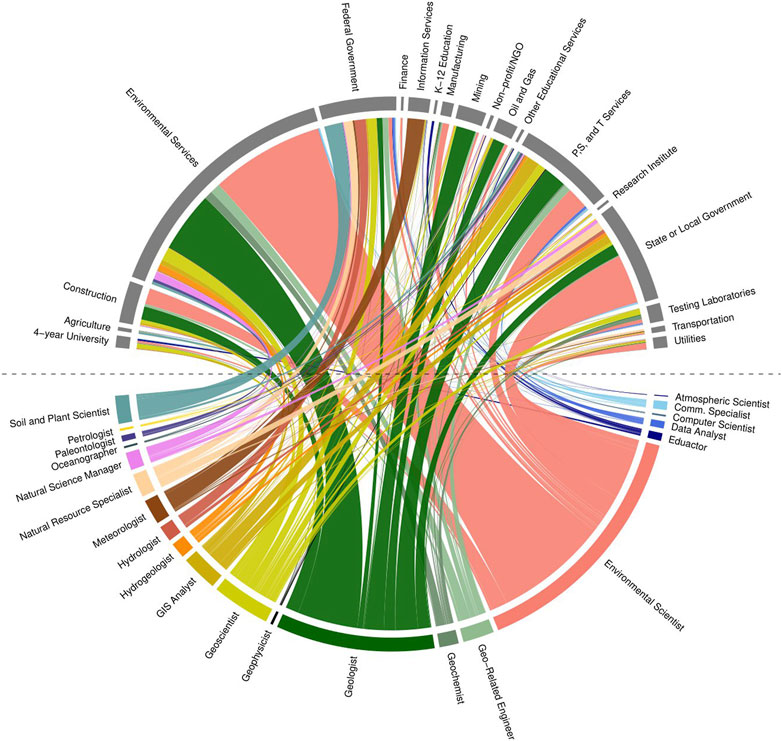

The 2,518 ads included in this study represent 19 geoscience industry sectors and 21 occupations (Figure 1). Most ads were published by environmental services, state and local governments, professional, scientific, and technical services, and the U.S. federal government (Figure 1). Environmental scientist, geologist, and geoscientists were the most common occupations (Figure 1). Of the occupations with >50 ads, soil and plant scientists and hydrology related positions are heavily represented by the U.S. federal government in our sample. Other occupations, such as environmental scientists and geologist are well represented across all industry sectors.

Figure 1. This figure was derived from the 2,518 job advertisements collected for this sample. The diagram depicts the distribution of occupations (shown below the dotted line), across different industry sectors (displayed above the dotted line). The size of the outer rim segments represents the proportion of ads for jobs in that segment relative to the others. The lines connecting the occupations and industry sectors indicate the relative distribution of ads from each occupation across the industry sectors.

Equal Opportunity Employer Statements

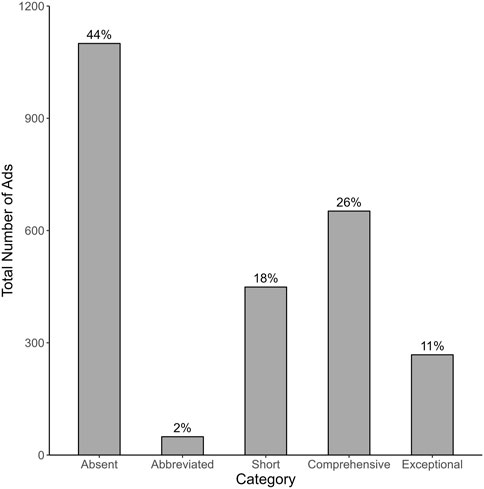

Just over half of the ads (56%) contained an Equal Opportunity Employer (EOE) statement (Figure 2). Generally, EOE statements were found near the end of the ad or well below the key job duties. We observed a few instances (<1%) where EOE statements were published near the top of the ad. Some EOE statements were listed as bullet points and some EOE statements were listed as full paragraphs or in their own section of the ad.

Figure 2. Bar graph displaying the number of ads coded for each equal opportunity employer (EOE) statement category. Refer to Table 1 for further category definitions and examples.

In the ads containing EOE statements, the largest proportion (26%) fall into the comprehensive category (Figure 2), in which EOE statements go beyond what is legally required but fall short of expressing that being an inclusive employer is a priority within the company or organization. Many of the comprehensive category statements we observed were copies of statements published by the EEOC for use by employers (United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1992). Eleven percent of ads contained EOE statements with exceptional language that expressed being an inclusive employer is a priority for the company or organization. Jobs with U.S. federal agencies overall had stronger EOE statements that provided, in detail, the commitment by federal agencies to creating an inclusive workforce.

Accommodation Statements

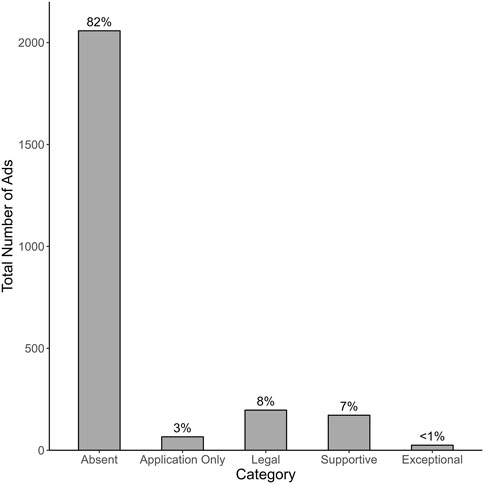

Only 18% of ads included an accommodation statement (Figure 3), with 3% of the ads only referring to accommodations associated with the application process. Rarely did employers advertise that they would take additional steps to make accommodations associated with performing the job duties. Most ads that provided accommodation statements were categorized as legal (8%) or supportive (7%) (Figure 3). Supportive ads provided statements such as “Reasonable accommodations, if available, will be made to enable individuals with disabilities to perform the essential job functions” and were usually placed near the listed job functions. Statements for ads in the legal category were similar to those in the supportive category, however, ads with legal category statements placed the burden on the applicant to request the accommodation and did not state if the accommodation would be made or considered.

Figure 3. Bar graph displaying the number of ads coded for each accommodation statement category. Refer to Table 2 for further category definitions and examples.

Physical Abilities

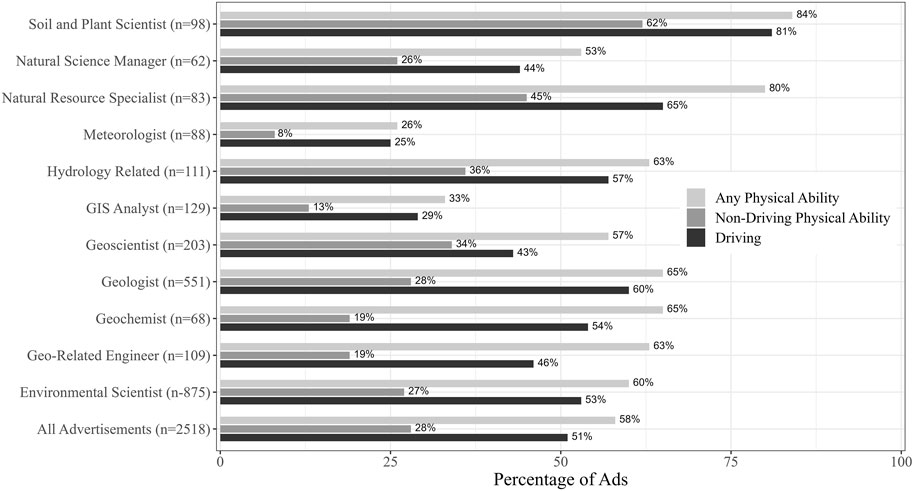

Fifty-eight percent of job advertisements requested a physical ability and 17% requested more than one (Figure 4). Driving skills were the most commonly requested physical ability, with 51% of ads requiring applicants to have a valid or current driver’s license or ability to drive a vehicle. Physical abilities other than driving (e.g., lifting heavy objects) were requested in 28% of ads. When broken down by type of position, the proportion of ads requesting a physical ability ranged from 26% of meteorologists to 84% of soil and plant scientists (Figure 4). Soil and plant scientist positions commonly request both non-driving physical abilities (61%) and driving-related physical abilities (81%). Only 13% of ads requesting a physical ability provided a statement saying the employer would make an accommodation for the applicant where possible.

Figure 4. Requested physical abilities for occupations with >50 ads. Occupations are listed alphabetically on the vertical axis and include the number of ads for each. Data are reported as the percentage of ads requesting any physical ability (driving, non-driving, or both), non-driving physical abilities (e.g., lifting heavy weight), and driving-related physical abilities. Percentage of ads requesting non-driving physical abilities and percentage of ads requesting driving-related physical abilities do not sum to the percentage of ads requesting any physical ability because some ads request both non-driving and driving physical abilities.

Sixty-three percent of the ads that request physical abilities did not include physical tasks in the core job functions. For example, several GIS Analyst positions requested the applicant be able to lift 25 pounds or more, yet all listed components of the job were computer-related tasks. Roughly 18% of ads requested physical abilities related to the job description, but it was unclear if the skills were required to be completed by the applicant. For example, some ads requested a valid driver’s license and did mention travel was required for the position. However, these ads also state that all work will be completed in teams and did not specifically say the applicant would be required to drive. An additional 18% of ads provided justification for why the physical ability was necessary (match category). Most of the ads in the match category requested non-driving physical abilities and provided clear reasons for why the applicant would need the skill. For example, one ad stated that “each member of the team must be able to carry ∼50 pounds of equipment across uneven terrain to locations that are inaccessible to motorized vehicles.”

Discussion

More than half of employers (56%) provided EOE statements, but the language used could be changed to be more welcoming to persons with disabilities. Of employers who provided EOE statements in their ad, most used statements provided by the EEOC without modification. While these short, formal statements are comprehensive in addressing a wide spectrum of marginalized groups, they lack originality and might not be attractive or appear sincere to diversity-minded applicants. As with any job seeker, people with disabilities desire to work at organizations that respect them and share their values. Employers who prioritize the inclusion of applicants with disabilities can establish a more effective and open channel of communication with them during the job application process. According to Padkapayeva et al. (2017), adopting a mutual accommodation model that recognizes and appreciates differences can facilitate open discussions between an employer, a worker with a disability, and other staff members to explore diverse approaches to task completion and perspectives. By including a well-crafted EOE statement in their job advertisements, geoscience employers could help alleviate the concerns of applicants with disabilities who may fear being discriminated against or denied employment if they disclose their disability. Furthermore, a positive EOE statement that demonstrates inclusivity will likely be appreciated by customers and employees without disabilities. This study did not investigate the perceptions that geoscientists with physical disabilities have of job advertisements; we assume, though, that geoscience employers could help alleviate potential concerns of applicants with physical disabilities by including a well-crafted EOE statement in their job advertisements.

Accommodation statements in the ads were scarce (Figure 3). A lack of information on accommodations in job advertisements reduces a disabled applicant’s ability to assess if they can perform essential job functions and can lead to significant employment barriers (Andreassen, 2021). Most ads that provided accommodation statements required the applicant to ask for accommodations and disclose their disability during the application processes without any signal of how likely an accommodation could be made. Given that many applicants with disabilities fear being discriminated against during the application process (McKinney and Swartz, 2021), being required to provide this information without any signal the employer is willing to make an accommodation may make applicants with disabilities feel disadvantaged even before applying.

Rarely in the ads did an accommodation statement clearly indicate that the employer wants to make their workplace accessible to people with disabilities. Such ads openly state the employer’s commitment to creating a working environment inclusive to people with disabilities, show they value people with disabilities in their workforce, demonstrate that an applicant’s disability would not impact their application, or provide detailed descriptions of the steps the employer takes to make their workplace inclusive. Additionally, employers with exceptional accommodation statements in their ads signaled they were willing to make accommodations from the application process through to employment. In their summary of research regarding workplace accommodations, Padkapayeva et al. (2017) found that providing accommodations for each phase of the employment process is critical for reducing barriers to the workforce for disabled applicants.

Fifty-nine percent of the ads requested a physical ability, meaning 41% of the ads require no physical ability to perform the job. This is contrary to the stereotype that a career in the geosciences is for the physically able. Additionally, of the ads that do request a physical ability, many did not demonstrate why the skill is necessary for the position. In particular, ads requiring a valid driver’s license for employment repeatedly failed to relate the ability to drive to the core job description. In the U.S., a driver’s license is frequently used as a proxy for many things such as identification or proof of residency (Denning, 2009) that may be unrelated to essential job duties. It is probable that ads requesting a valid driver’s license, even though driving is not part of the job requirements, are doing so for reasons that are not related to driving, such as a prerequisite for being included on the company’s insurance policy. When job advertisements ask for physical abilities that are not related to the actual job requirements, it could be difficult for applicants with a disability to determine if they have the necessary skills to perform the essential job functions. Given that such a significant portion of the ads in this study (41%) do not require a physical ability, and that the physical abilities requested in many ads do not seem to align with essential job functions, there should be many opportunities for persons with physical disabilities to be successful in the geoscience workforce.

Despite the benefits employers experience from creating an accessible workplace, some employers may not believe the benefits outweigh the costs of hiring individuals with disabilities. For example, workplace accommodations are necessary for some individuals with disabilities to achieve and maintain employment (Nevala et al., 2015), but those accommodations are provided at the expense of the employer. However, when workplace accommodations are provided and properly executed, their benefits often surpass their expenses (Solovieva et al., 2011) by having employees with higher levels of job satisfaction, commitment, and performance (Tworek et al., 2020), and by increasing diversity and gaining a positive image for the company (Kochan et al., 2003). Additionally, many people with disabilities are able to find and maintain employment with low-cost, low-technology accommodations that are inexpensive to the employer (Solovieva et al., 2011).

Conclusion

This study highlights how current online geoscience job advertising practices could present employment barriers to people with physical disabilities. Specifically, the geoscience community should be concerned by the current use of equal opportunity employer and accommodation statements in entry-level geoscience job advertisements, and by the frequent failure of employers to demonstrate how requested physical abilities are necessary for an advertised position.

Efforts to ensure that geoscience fields are welcoming and accessible to people with physical disabilities must address barriers to entry in geoscience careers, as well as the development of a more inclusive and culturally responsive workplace. A logical start for employers includes creating job advertisements with clear and explicit statements of equal opportunity employment and accommodations and that clearly link the physical abilities they request and the essential job duties. Additionally, geoscience departments can help make students with physical disabilities aware of potential barriers they may encounter when job hunting and can highlight career options that will value their abilities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

GS contributed to data collection, data analysis, creation of figures and tables, and creation of the manuscript. GS, KV, and AE contributed to the methods used in this study and revising of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Americans with Disabilities Act (1990). Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. § 12101. Available at: https://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm (Accessed March 01, 2023).

Andreassen, T. A. (2021). Diversity Clauses in Job Advertisements: Organisational Reproduction of Inequality? Scand. J. Manag. 37 (4), 101180. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2021.101180

Atchison, C. L., and Libarkin, J. C. (2016). Professionally Held Perceptions About the Accessibility of the Geosciences. Geosphere 12 (4), 1154–1165. doi:10.1130/GES01264.1

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). National Center for Health Statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0816-disability.html (Accessed March 01, 2023).

Denning, S. R. (2009). The Impact of North Carolina Driver’s License Requirements and the REAL ID Act of 2005 on Unauthorized Immigrants. Pop. Gov. 74 (3), 1–14.

Hampson, M. E., Watt, B. D., and Hicks, R. E. (2020). Impacts of Stigma and Discrimination in the Workplace on People Living With Psychosis. BMC Psychiatry 20, 288–311. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02614-z

Harper, R. (2012). The Collection and Analysis of Job Advertisements: A Review of Research Methodology. Libr. Inf. Res. 36 (112), 29–54. doi:10.29173/lirg499

Indeed (2023). Transparent Pricing for Better Hiring. Available at: https://www.indeed.com/hire/o/pricing?gclid=Cj0KCQiAmNeqBhD4ARIsADsYfTc9TgG-E5yrQIxwU8vLg18LcM5ZZW7zbbAxJAwC8hkL11oenuophHYaAtdlEALw_wcB&aceid=&gclsrc=aw.ds (Accessed November 12, 2023).

Karpatne, A., Ebert-Uphoff, I., Ravela, S., Babaie, H. A., and Kumar, V. (2018). Machine Learning for the Geosciences: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 31 (8), 1544–1554. doi:10.1109/tkde.2018.2861006

Kingsbury, C. G., Sibert, E. C., Killingback, Z., and Atchison, C. L. (2020). “Nothing About Us Without Us:” the Perspectives of Autistic Geoscientists on Inclusive Instructional Practices in Geoscience Education. J. Geoscience Educ. 68 (4), 302–310. doi:10.1080/10899995.2020.1768017

Kochan, T., Bezrukova, K., Ely, R., Jackson, S., Joshi, A., Jehn, K., et al. (2003). The Effects of Diversity on Business Performance: Report of the Diversity Research Network. Hum. Resour. Manag. 42 (1), 3–21. Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management. doi:10.1002/hrm.10061

McKinney, E. L., and Swartz, L. (2021). Employment Integration Barriers: Experiences of People With Disabilities. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32 (10), 2298–2320. doi:10.1080/09585192.2019.1579749

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) (2023). Diversity and STEM: Women, Minorities, and Persons With Disabilities 2023. Special Report NSF 23-315. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation.

Nevala, N., Pehkonen, I., Koskela, I., Ruusuvuori, J., and Anttila, H. (2015). Workplace Accommodation Among Persons With Disabilities: A Systematic Review of its Effectiveness and Barriers or Facilitators. J. Occup. Rehabilitation 25, 432–448. doi:10.1007/s10926-014-9548-z

Padkapayeva, K., Posen, A., Yazdani, A., Buettgen, A., Mahood, Q., and Tompa, E. (2017). Workplace Accommodations for Persons With Physical Disabilities: Evidence Synthesis of the Peer-Reviewed Literature. Disabil. Rehabilitation 39 (21), 2134–2147. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1224276

Robert, P. M., and Harlan, S. L. (2006). Mechanisms of Disability Discrimination in Large Bureaucratic Organizations: Ascriptive Inequalities in the Workplace. Sociol. Q. 47 (4), 599–630. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00060.x

Shafer, G. W., Viskupic, K., and Egger, A. E. (2023). Critical Workforce Skills for Bachelor-Level Geoscientists: An Analysis of Geoscience Job Advertisements. Geosphere 19 (2), 628–644. doi:10.1130/GES02581.1

Solovieva, T. I., Dowler, D. L., and Walls, R. T. (2011). Employer Benefits From Making Workplace Accommodations. Disabil. Health J. 4 (1), 39–45. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2010.03.001

Tworek, K., Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A., and Kamiński, R. (2020). Workforce Diversity and Organizational Performance: A Study of European Football Clubs. Argum. Oeconomica 45 (2), 189–211. doi:10.15611/aoe/2020.2.08

United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1992). EEOC Compliance Manual. Washington, D.C.: United States of America: U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018). Standard Occupational Classification Systems. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/soc/2018/major_groups.htm (Accessed July 02, 2022).

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023). Persons With a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf (Accessed March 02, 2023).

Von Schrader, S., Malzer, V., and Bruyère, S. (2014). Perspectives on Disability Disclosure: The Importance of Employer Practices and Workplace Climate. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 26, 237–255. doi:10.1007/s10672-013-9227-9

Keywords: people with disabilities, physical disabilities, accommodation practices, geoscience workforce, job advertisements

Citation: Shafer GW, Viskupic K and Egger AE (2024) Geoscience Job Advertisements as a Barrier to Employment for People With Disabilities. Earth Sci. Syst. Soc. 4:10086. doi: 10.3389/esss.2024.10086

Received: 30 April 2023; Accepted: 07 March 2024;

Published: 20 March 2024.

Edited by:

Aisha Al Suwaidi, Khalifa University, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Melanie Finch, James Cook University, AustraliaCaitlin Callahan, Grand Valley State University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Shafer, Viskupic and Egger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: G. W. Shafer, Z3JlZ3NoYWZlckB1LmJvaXNlc3RhdGUuZWR1

G. W. Shafer

G. W. Shafer K. Viskupic1

K. Viskupic1 A. E. Egger

A. E. Egger