- 1School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2Unit for Institutional Change and Social Justice, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

For minority employees at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), the organisation has enriched their careers, while offering equality, diversity and inclusivity (EDI) measures to mitigate some of the issues affecting them. However, the way they belong to BAS remains impacted by the structural and everyday practices that shape their lives through identity processes. In light of BAS’ ambition to enhance Antarctic science opportunities to underrepresented groups, this study engages with the lived experiences and perspectives of minority BAS employees at their workplace. We argue that while they experience and perceive rejection, discrimination and exclusion, these practices are tangled up in the dominant and majority group’s internal identification processes rather than by the isolated and deliberate action of its members. Those who are part of the “unmarked” dominant group have, from an early age, internalised national, ethnic, gender, and other forms of belonging and continue to engage in new boundary demarcation in the present. In this way, it is in their contact with non-members, that the boundaries between the “marked” and “unmarked” come to the fore, even when the intention of the dominant group may be to erode such boundaries.

Introduction

In a world facing long-term climatic change, resource depletion and energy insecurity, the ability of the scientific research sector to build a sustainable future for all is intrinsically linked to the individual scientists involved (Gibbs, 2014). Science’s capacity to address these contemporary challenges is also inextricably tied to the Polar regions as the Earth’s so-called “barometers” for climate change, in both the figurative and literal sense, for a variety of economic, social and political discourses (Wehrmann, 2016). In the United Kingdom, polar research is tightly linked with the British Antarctic Survey (hereafter BAS). Originally an ad-lib wartime naval operation, and later a post-war political exercise, BAS transformed into an organisation dedicated to scientific research and discovery following the commencement of the Antarctic Treaty in 1961 (Fuchs, 1982). In the 60 years since, BAS has made its name as Britain’s national Antarctic operator; with bases and specialist facilities in the United Kingdom, Arctic, Antarctic and the Falkland or Malvinas Islands, the organisation, at present, assumes responsibility for most of the UK’s polar science research (British Antarctic Survey, 2015a). But, the history of BAS cannot be disentangled from global colonial relations.

Similar to other players in international relations such as the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) (see Bar-On and Escobedo, 2019) or National Geographic (see Lutz and Collins, 1991; 1993; Escobedo, forthcoming), BAS’ origins can also be linked, from a postcolonial perspective, to an entanglement of global colonial relations. The 1943 Operation Tabarin, the secret British expedition that would give origin to the Falkland Islands Dependency Survey (FIDS) that turned into BAS in 1962, had the characteristics of a colonial project. It was carried out as part of the British imperialist agenda that up until the 1960s still held most of its colonial territories. Like football has played a “civilising” role (Hutchison, 2009) and photography has operated as a tool to interpret difference (Butler, 2005, p. 823), both simultaneously emphasising Western (and white) superiority, scientific research and related tasks undertaken in Antarctica as part of Tabarin, and later as FIDS and BAS, functioned as a form of territorial control. Indeed, the administration of British government operations in Antarctica is still conducted using the colonial model, with the British Antarctic Territory being governed by a London-based commissioner based in London, who has the power not only to enact laws but to appoint the judges, magistrates and coroners responsible for enforcing these laws (British Antarctic Treaty, 2020). Not least, just as it happened with the position of editor-in-chief in National Geographic until 2014 (National Geographic, 2018; Wamsley, 2018), before 2013 only highly-ranked white, male scientists have held the Directorial post at BAS.

Presently, if BAS is taken as a proxy for UK polar research, just 3% of the workforce belong to minority ethnic groups, 2% identify as LGBTQ+ and people with disabilities make-up only 1.8%, according to Frater (2021). These statistics do not align with the UK’s demography, where minority ethnic, LGBTQ+ and disabled individuals account for 13%, 6% and 18% of the total population, respectively (ONS, 2013; 2021). Thus the UK polar science community is not representative of the wider society that it serves (Griffiths et al., 2022), from a statistical perspective. Gibbs (2014) suggests that for UK polar science institutions to become more accessible and equitable they must target and recruit a combination of individuals coming from both well-represented and underrepresented backgrounds, especially if polar research is to remain timely, relevant and innovative in the future.

For Bentley et al. (2021), it is self-evident that building diversity in UK polar science requires investment in people. BAS does officially express its commitment to a “workplace that is fair and inclusive, and which welcomes diversity,” one that, over the past decade, has been materialised in a range of equality, diversity and inclusivity (EDI) initiatives. This includes the creation of the Polar Pride Network in solidarity towards LGBTQ+ individuals (British Antarctic Survey, 2020); membership of the Athena Swan Charter in support of gender equality (British Antarctic Survey, 2018); adoption of the Disability Confident scheme in favour of people with disabilities and health conditions (British Antarctic Survey, 2018); and the Polar Horizons project supporting the introduction of underrepresented early career researchers to polar science (Griffiths and Muschitiello, 2021), among others.

However, what does this “commitment” actually mean and what does it look like in practice? To address this question, BAS HR commissioned the first author of this paper to undertake the Minorities at BAS (hereafter MiBAS) project. It explores the experiences and perspectives of minority BAS employees to:

I. Understand their perceptions of BAS as workspace and community;

II. Identify the challenges to access, participation, and success that are frequently encountered by them;

III. Recognise the way these challenges lead to material consequences in the professional and personal lives of minority employees; and

IV. Distinguish the identification strategies for representation, and participation that these employees develop at BAS, the polar sciences, and academia, to mitigate the challenges that affect them in particular, and erode the boundaries between them and the dominant group.

These objectives are congruent with BAS’ ambition to promote and enhance Antarctic science opportunities to underrepresented groups, hence achieving them can potentially serve to influence the leadership and culture of the institution. However, this does not mean that the analysis herewith presented has been agreed upon, mandated, or regulated by the institution in question. Quite the opposite. The goal is to assess in a disembedded manner how BAS’ social space is being shaped in terms of equality, diversity, and inclusivity, and whether within said space the perspectives of those identified as part of non-dominant ethnic, gender, physical, mental and other groups have a chance to impact combined thinking and understanding.

This paper thus discusses that while BAS promotes EDI initiatives, these focus mostly on avoiding direct discrimination and broadening formal access to the workspace for people that are underrepresented in polar sciences. These individuals do consider that their employment at a highly regarded institution like BAS comes as a great advantage in their careers. However, and as we will show, they also experience and perceive that the boundaries between them and the dominant or core group are still at least informally delineated, and organised hierarchically, even when both parties hold equivalent positions. In their understanding, this strengthens and perpetuates an asymmetric relation between them, makes EDI policies short-sighted, and has an impact on their career development.

By engaging with the experiences of minority employees at BAS, we observe that they are in fact exposed to persisting forms of rejection, discrimination, and exclusion, even if these are mostly covert. We argue that these practices, and the beliefs that endorse them, are primarily tangled up in the internal identification processes by means of which the members of the dominant and majority group have become part of said collective in the first place. In this way, they are not necessarily isolated, but rather enmeshed in the dominant group’s internalised national, ethnic, gender, and other forms of belonging, and their corresponding identity markers (micro level); and in the continuous process of boundary formation in the hands of institutions (meso level). While rarely ill-intentioned, these identificatory practices are carried out rather unreflectively, and with that in manners that are often insensitive to the actual necessities of the non-members. In this way, they permeate, order, and structure BAS’ social environment, and the wider space of UK polar science.

Conceptual Aspects: Unmarked Spaces

The Herderian discursive order concerning ethnic relations that once dominated social sciences asserted that people, ethnic groups, and nationalities are well-bounded entities with a specific cultural heritage, internal solidarity, and common sense of identity (Wimmer, 2013, pp. 16–44; see also Kiss, 2018a, p. 6; Kiss, 2018b, p. 401). This paradigm would associate ethnic boundaries with place or locality, while perceiving said boundaries as rather monolithic and homogeneous entities separating various groups. The constructivist turn has challenged this perspective (Jenkins, 2008a, pp. 10–16; Wimmer, 2013, pp. 22–31). Attention has shifted “from groups to groupness as variable and contingent rather than fixed and given” (Brubaker, 2004, p. 12). As per boundaries, the focus has moved from the “content” to the processes that define identities (Barth, 1998).

Understanding identity from a constructivist perspective, Jenkins (2000, 2008b) makes a useful analytical distinction between self- or group identification, and social categorisation. The author describes the first as an inward process of group making, where ingroup membership is preceded by mutual recognition and the emphasis on similarity among different individuals. The second, for its part, is an outward process where difference is emphasised, categories are externally ascribed to others, and those categorised do not necessarily recognise each other as part of the same collective, often not being aware of their categorisation at all. Self- or group identification, and categorisation, work interdependently in the construction of collective identities (Jenkins, 2000; Jenkins, 2008b). They shape people’s lives and experiences (Jenkins, 2008b), and lead to material consequences (Jenkins, 1983), at times pernicious to one’s individuality, humanity, and life projects (Kurzwelly and Escobedo, 2021). The focus of this paper is precisely to understand how the social space provided by a research institution can also shape the dominant ingroup vis-a-vis its outgroup, through internal and external identity and boundary making processes. The concept of groupness is thus useful here.

Constructivist scholars have defined groupness, in the sense of group solidarity and shared identification, in multiple ways (see Brubaker, 2004; Brubaker et al., 2006; Wimmer, 2013). At the micro-level, Wimmer (2013) sees it as a consequence of having stronger and more frequent in-group relations vis-a-vis weaker and less frequent intergroup relations—the author argues that besides groupness, also the “closure” for which a group opts as a consequence of the rejection, discrimination, and exclusion exercised by a dominant collective, adds to this process. When treated as a meso-level phenomenon, groupness is understood in terms of the impact that institutions have on the micro-level through the shaping of individual actions and self-perceptions (Lamont et al., 2016, pp. 22–27). This involves a psychological aspect of groupness dealing with self-identification from an early age, and a social one concerning group boundaries, both built on a social space shaped by interrelated institutions and that guides the developing group members to a high level of socialisation, consciousness, and identification (Kiss, 2018a, p. 8).

The psychological aspect points at the internalisation of ethnic belonging as personal feelings and experiences, and that of its markers, for example, language, accent, or religion, since childhood (Fenton, 2003, p. 88; Jenkins, 2008a, p. 48; see also Dunn, 1988; Jenkins, 2000; Kaye, 1982). From a critical constructivist position, this process is conducive to social identifications and boundaries that are constructed, but at the same time also solid (Brubaker and Cooper, 2000; Brubaker, 2004). As per the social aspect of groupness, it relates to the continuous role of institutions in demarcating and maintaining boundaries (see Lamont and Molnár, 2002; Wimmer, 2013; Lamont et al., 2016; Kiss et al., 2018).

To speak about a group, the identification and boundaries of which are endorsed by BAS, in the context of asymmetries such as those between majority and minority, or overrepresented and underrepresented, employees, we turn away, again, from the Herderian paradigm and focus this time on the integrationist discursive order. From an integrationist perspective, the social world is divided between an ethnically “unmarked” “social mainstream,” and various ethnically “marked” groups (McGarry et al., 2008; Kiss, 2018b, p. 402). Hidden by the discursive order, the core group is seen as devoid of well-bounded contour, and the institutionally crafted social space that it occupies becomes one where this group can reproduce itself ethno-culturally without the burden of boundary making and maintenance, or the need to be “ethnic” in its “purpose or goals” (Kiss, 2018b; Kiss and Kiss, 2018, p. 235). Belonging to it means to be taken for granted, regarded as usual, normal, or natural (Kiss, 2018b). For those standing on this side, belonging to a minority or non-core group hence means “an unusual attachment to something defined as particular,” exceptional, marked (Fenton, 2003; Kiss, 2018b, pp. 403–404, 421; see also Brubaker et al., 2006, pp. 211–217). Here, linguistic articulations play an important role. Lotman’s (1990) distinction between the cultural centre and the periphery of what he calls the “semiosphere” is thus a useful tool for analysis.

The semiosphere is the semiotic space that provides “the necessary conditions for the existence and functioning of languages” (Mladenova, 2022, p. 11), “outside of which semiosis itself cannot exist” (Lotman, 2005, p. 206). For Lotman (1990, pp. 128–129, 141), there is a European semiosphere the cultural centre of which produces a dominant cultural grammar, or set of dominant norms, perceived as “common to all,” “normal,” or unmarked. Dyer (1997) and Garner (2007) relate this concept to whiteness. Butler (1993, 1999) similarly articulates the concept of heterosexual matrix to refer to the space of intelligibility from which “sexed” bodies are assumed, constructed, and brought into existence. From the perspective of the cultural centre, the norms developed at the periphery are seen as deviant, or marked (Lotman, 1990, p. 141; Mladenova, 2022, p. 13).

Like with ethnicity, the constructivist perspective applies similarly to other identifications (Jenkins, 2008b, p. 119). So does the term “markedness” not only describe the category of marked and unmarked in ethnic or cultural terms; it also does it in relation to gender, sexual orientation, and ableness, among others (Waugh, 1982). Additionally, a category may be marked in one social context, but unmarked in another one (Brubaker et al., 2006; Kiss, 2018b, pp. 403–404). Following this, in this article, we propose the term “unmarked spaces.” With this, we do not intend to merely identify a context where an integrationist discourse operates to distinguish the unmarked and the marked groups and individuals. The idea is, most importantly, to make visible and emphasise the contentious and dynamic nature of the social space provided by institutions, which while not expressly having (ethno)political goals nonetheless participate in the formation and maintenance of an in-group as dominant and unmarked. Unmarked spaces are thus spaces the ownership of which is unreflectively assumed to be in the hands of the dominant culture, and where the bearers of internally or externally ascribed identities deemed as unusual and exceptional are marked, and their voices may often become untrustworthy, unworthy, or “difficult to understand” (Fricker, 2007).

Figuratively speaking, in a parking lot, the unmarked spaces are not the spaces people occupy because they necessarily have a burden to reflectively and deliberately produce and maintain an identification or boundary, for example, that of the able-bodied. They occupy them because they are aware of the existence of another type of space that is marked with a sign, indicating that it is reserved for those who are not able-bodied - unlike them -, and that is protected by the law—often also by social norms. They would thus rarely reflect on the fact that their mainstream identity has also been constructed, even less so that a set of institutions are behind its making. Instead, they see themselves as usual, normal, or natural, that is unmarked, and approach the world and others from that position.

In our example, the able-bodied driving around a parking lot would normally assume, unreflectively, that they are the absolute or, at least, large majority hence expecting there to only be so many disabled parking spaces. They may also consider disabilities to be exclusively physical. Moreover, where, on a busy day, the disabled parking spaces are the only ones not being occupied, attitudes and behaviours denoting rejection and discrimination may suddenly arise. Some may manifest this in the assumption that these spaces “must be” occupied, and that if not, then those to whom they have been assigned are “carelessly” not taking full advantage of the resources allocated to them, or may be “unfairly” taking “our” spaces, hence are “out of place” (Puwar, 2004), or somehow “out of order” (Berry et al., 2017, p. 546). Depending on the level and form of surveillance used in and around a parking lot, among other factors, one cannot exclude the occasional able-bodied driver and/or passenger using this narrative as an argument to transgress. As for the scenario where the disabled individual does not find a free space among those few allocated to them, using unmarked spaces can be a challenging process for the very reasons that led to this allocation in the first place, hence putting this individual back in a cycle of disadvantages.

Applying an integrationist approach to the analysis of the social space shaped at BAS does not only allow us to visualise the power relations existing between a dominant group located at the cultural and epistemic centre and a non-dominant group placed at its periphery. It also allows us to provincialize said dominant group by addressing the social spaces that shape it as “unmarked”—it is about marking the unmarked group. By this means, we can, first, refocus the attention from the institution’s non-dominant to its dominant group as the main object of observation and analysis. Core group members are now identifiable, recognised as sharing a cultural background, reinterpreted in ethnic terms, and ultimately also considered as targets of diversity management initiatives, while their core positionality is highlighted. Second, to emphasise the dynamic nature of the identification processes undertaken by the dominant group in relation to non-dominant and underrepresented positionalities coexisting within BAS. This includes, for example, situations of injustice and violence, as well as situations of boundary porosity and erosion. Third, to read BAS as part of a network of institutions that create a suitable social space for the core group to operate as a default “unmarked category.”

Fourth, this approach also allows us to understand that while the non-dominant, or “marked,” groups and individuals sharing the same social space at BAS are also the product of self-/group identification, external categorisation impacts their individual and group experience more significantly at this institution. In this way, they are not merely minorities in the self-identificatory sense, but are also, and more often than not, the product of minoritisation. Selvarajah et al.’s (2020, pp. 2–3) “minoritised,” including “minoritisation” and related terms, can be associated with Mylonas’ (2013, p. 27) “non-core group.” Both terms emphasise power relations and, unlike in the case of official “minorities”, those in the less powerful side of the relation are not necessarily mobilised around their collective identification in an official or legal sense. Thus, for these authors, “non-core” and “minoritised” emphasise a dynamic process transcending the minority/majority binary. While non-core or minoritised collectives may at times constitute a numerical majority, they still represent a position of less advantage in relation to the dominant group as a consequence of long-standing socio-historical structures (Mylonas, 2013; Selvarajah et al., 2020; see also Brah, 2005; Gunaratnam, 2003). Where we distinguish these terms is in that “minoritised” individuals may be less conscious of their (type of) difference, yet still make up a collective in the dominant group’s gaze. Considering this, “minoritised” can also embrace other terms, such as “racialised” or “sexualised.”

Methodology

Empirical Aspects and Compliance With Ethical Principles

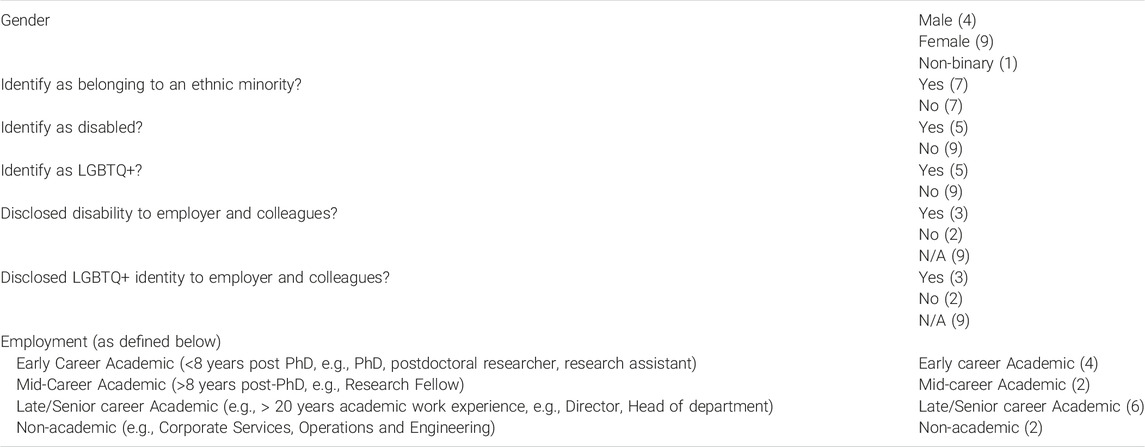

Advertising of the MiBAS project was carried out primarily through BAS organisational mailing lists in November 2021. Interested individuals were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews themed around their experiences and perspectives on EDI initiatives at BAS in the subsequent months. The participants self-identified as minority ethnic, disabled, LGBTQ+ or combinations of these identities (see Table 1). Some participants had disclosed their minority identities to both their colleagues and employer, others had not, whilst those with intersectional characteristics were often selective with which aspect of their identity they chose to disclose. Those interviewed had also different areas of employment and career stages.

All interviews took place via video conferencing through Zoom software in November-December 2021. Considering that this research involves human participants, including potentially vulnerable people, free and fully informed consent was obtained from all interviewees. This entailed that their participation was voluntary, done without coercion, and that it could be refused at any phase of the process without consequences. The participants were also assured that their personal information and data would be protected through anonymity or pseudonymity, hence making them unidentifiable before the groups targeted for the dissemination and exploitation of this research.

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim and subsequently anonymised. The interview content was analysed using Nvivo software to identify and compare key emergent themes. Following Braun and Clarke (2012), the authors employed a six-stage approach to thematic analysis. Both authors independently coded a sample of the transcripts, discussed the content and then established the preliminary codes. Following detailed re-reading of the interview transcripts, the authors then coded the remaining data, and these codes were then adjusted, combined and refined to establish key emergent themes. Once the key themes were collated, the interview transcripts were returned to and the themes reviewed. This final set of themes formed the basis for interpreting the findings, while encompassing the richness of the MiBAS participants’ experiences.

I. Core group’s identity processes and boundary making;

II. BAS’ unique yet challenging institutional environment, and hierarchical structure; and

III. Minority agency, new boundaries, and future hopes.

These themes characterise the experience of BAS minority employees in front of their mainstream colleagues, and the practices that regulate the institution - with emphasis on those related to EDI. Engaging with experiences functions “as a way of talking about what happened, of establishing difference and similarity, of claiming knowledge that is ‘unassailable’” (Scott, 1991, p. 797). The idea of conducting interviews exclusively with minority BAS employees was to engage their voice in the identification, description, and explanation of their individual experiences. It was a way of exploring their awareness of their own positionalities and peripheral status vis-a-vis those of their colleagues, and their institution. It was also a way of understanding how the interviewees expressed intent and exercised agency (e.g., identification strategies) in relation to the general conversation on equality, diversity, and inclusivity in and beyond their workspace. Relatedly, it was important to recognise any participatory element during interviewing, e.g., collective identification, will, or action across interviewees or in their contact with interviewers - not least considering that both authors are identified with groups or categories that are underrepresented at their respective research fields, workspaces, and social environments.

Finally, the authors acknowledge that this work could have benefited from the participation of BAS core-group members. However, the principal intent of this research is to create a safe space for the voices of non-core employees to be listened to. Thus, through their own voices, they could illustrate what the material consequences of their persisting categorisation have been, how their lives and experiences have actually been affected and shaped by practices that are primarily intended to serve them, and how they, as individuals identified with a variety of minority groups, conform an all-embracing boundary at an institution like BAS and UK polar science.

Results and Discussion

Core Group’s Identity Processes and Boundary Making

From the interviews with minority BAS employees, we observed that while access to a prestigious scientific community has generally brought them closer to the core and majority groups dominating that space, it has also enabled the exposure and further demarcation of the boundaries that divided them in the first place. Forms of rejection, discrimination, and exclusion have permeated this process in covert, subtle, and unreflective, rather than direct or explicit, manners. This, we argue, relates more to the internal identification processes shaping the dominant group in and beyond the institution, and how it approaches others from its tutored position. Comments made by several of the interviewees illustrate this idea:

“I think… there is a fear from a white, all white middle class almost workplace of not overt racism, but not knowing how to deal with people from ethnic minorities, for example, or religious minorities and not knowing how to even have the conversations and things.” (MB6)

“If there’s 35 scientists on the ship, or 24 or something like that, if one of them is not having a good time it’s easier to think “why did they come with that attitude?,” or “why are they like that?,” rather than to think “what are we doing?”.” (MB6)

“It comes down to workplace culture and that’s not necessarily something you can just change overnight … when you’re surrounded by people who are not quite the same as you, or don’t necessarily understand something, you don’t want to have to explain it to them.” (MB9)

“Although I’m very fond of my colleagues, sometimes it is hard, it’s isolating, that they can’t deal with so many things, that they can’t even acknowledge so many things that are day to day realities for me.” (MB10)

These excerpts point at the unreflective way in which BAS’ core group members relate to those with identifications perceived by them as unusual, or exceptional. Their apparent lack of knowledge, experience, reflectivity, sensitivity, and acknowledgement in communicating with those bearing seemingly distant identity markers, speaks to how, from a centre endowed with taken-for-granted cultural grammars and norms, non-dominant (peripheral) identities are perceived, and shaped (see Lotman, 1990; Mladenova, 2022). This is at the centre of Fricker’s (2007) epistemic injustice, where one is wronged in their condition as “knower,” whether because their voice is rendered by epistemic authorities as untrustworthy or unworthy due to categorization (testimonial epistemic injustice), or as “difficult to understand” due to the lack of vocabulary (hermeneutical epistemic injustice). The above-mentioned testimonies also show a situation that, according to Lyotard (1988, xi, p. 13), is provoked by the absence of a universal rule of judgement enabling litigation to take place among disputing parties and making their conflict resolvable. In short, minority members feel that they are not being taken seriously or understood, and that addressing this matter is likely to not lead anywhere.

By identifying a dominant group and attributing to it the incapacity and insensitivity in the understanding of the nuances in the lives, experiences, and stories of those outside of it, the statements above attest to said group’s deep-seated self-identification as part of the “unmarked” social mainstream. As the next excerpts will illustrate, physical or behavioural traits associated with Britishness, perceived whiteness and heterosexuality, practiced and exposed heteronormativity, physical ableness, and related markers of identification tend to characterise the social mainstream, while conferring it privilege. Whilst maintaining this group’s boundaries, material consequences are incurred by its non-members. The latter are in turn categorised to be “recognisable” (Butler, 1997, p. 5); they are shaped and so brought into or kept within certain social hierarchies, and their plurality and diversity simplified and distorted (Kurzwelly and Escobedo, 2021, p. 2). The following excerpts illustrate how categorisation affects people’s lives and experiences materially in the context of unmarkedness:

“I’ve heard things in the past, like someone say that someone with depression, wouldn’t be able to lift heavy equipment […] I’ve also heard people say “Oh well, you know, there are reasons that people with disabilities can’t go to Antarctica,” and when you press them it’s like “Well, I was thinking about physical disabilities”.” (MB5)

“You’ll see people feeling quite excluded if they are from a minority, not because people are deliberately excluding them, but the fear of saying the wrong thing or things has definitely made people leave someone in a headscarf sitting on their own.” (MB6)

“I’m on the spectrum of … LB etcetera and I’ve never been out at all because … I just felt I had too many problems already! They already had to cope with me being female … they were having cope with me not being as English as, or as British as they were in some way … and I didn’t, you know I just felt I had enough, kind of, things that they were having to deal with round me that I didn’t … I don’t even go there.” (MB10)

“People understand overt racism and they understand overt sexism, and I think our cases of that are limited. But it’s those institutional ways, practices, it’s the language that’s kind of underlying […] particularly an organisation, where you know women weren’t allowed to go south until fairly recently and was very male dominated … things that’ve just grown up in that culture that have just kind of stuck around.” (MB10)

“There’s an inherent bias against disabled people within an organisation like BAS because of “must be physically fit to go places” and things like that.” (MB13)

These testimonies highlight how categorisation can create the conditions for concrete material consequences to take place. They range from the avoidance to engage in daily conversations with minority colleagues, leading up to, e.g., the latter’s isolation, all the way to the seeding of bias at the workspace, leading up to, e.g., the unconscious exclusion of certain minorities from research field trips. Only in a few cases, participants made a direct and explicit connection between categorisation and underpayment: “In terms of gender equality, racial equality, disability equality—we know that all those groups can end up being underpaid” (MB5). Similarly, only a few times, job insecurity or the lack of promotion were suggested as a consequence of categorisation: “I’m sort of still going from contract to contract to contract, one reason will be because of all my intersectional identities” (MB10).

The testimonies above indicate the presence of a limited understanding of overlapping patterns of discrimination and intersectionality (Tzanakou, 2019; Lawrence, 2022), and with that the de facto homogenisation of the category “women” (Seag et al., 2020):

“There is a lot more support for some groups within BAS and some of it has come recently with trying to do the whole women at BAS and women in science sort of thing … I had to fight for years to get a training course in leadership, whereas it was offered to women ahead of me.” (MB6)

Privileging of gender above other aspects of minoritization in policy making regarding equality is widely reported in the literature (Bhopal and Henderson, 2019; Johnson and Otto, 2019; Johnson, 2020). Indeed, many of the female participants described how the drive for gender equality at BAS has made the space more accessible (MB9: “my team is almost all female”; MB10: “the battle was basically kind of won, the argument was that women should be allowed to overwinter” [in Antartica]), improved the value of the category woman (MB2: “Women used to have it more difficult”), and blurred the boundaries between women and the social mainstream (MB10: “people said “it’s not fair you’re just talking about women”—but it was to my benefit that they wanted to talk”).

Besides the privileging of gender above other aspects of minoritisation, reductionist positions were also observed by the participants in relation to disabilities. Most interviewees, regardless of whether or not they self-identified as disabled, reported poor disability representation across the various BAS workspaces. Returning to the metaphor of the parking lot, in the excerpts shown above bias is manifested as a reaction to the way in which a previously familiar physical space has been reorganised to become unusual (i.e., equitative, inclusive) to the dominant group. In the perspective of the interviewees, majority members see disabilities as exclusively physical, guard the boundaries of the shared spaces and ascribe to themselves the right to control them, feel transgressed by the unusual, and have little objection to others being excluded or put in disadvantage. For the mainstream, the unusual (e.g., people, vocabularies) must be marked to be intelligible in their dominant gaze, and passively confined to an allocated marked space, located at the periphery of their mainstream space: “I’ve also been in situations where people have said, “oh we haven’t got any disability representation in the room” and I’m kind of sitting there thinking oh so what am I then?” (MB5).

BAS’ Unique Yet Challenging Institutional Environment, and Hierarchical Structure

A common feature of the narratives of all the participants was their perception of BAS as a unique institutional environment to be employed in, where scientists get to address “big problems,” “big, big issues,” and “a lot of big scientific questions” (MB13). Many of them identified the collaborative, transdisciplinary research taking place at BAS as its “real strength” (MB1), as what makes it “a good place to do research” (MB14). This perspective also applied beyond BAS’ headquarters. A number of participants were imbued with a sense of excitement over the chance to conduct fieldwork in the polar regions, considering it “special,” “a privilege,” and “a big draw” (MB2), or “a really special opportunity” (MB3).

However, the acknowledgement of the benefits that BAS brings into the lives of its employees does not exclude, for most participants, the fact that there are important institutional challenges to be addressed. For many of them, these may be congruent with the inherently competitive nature of BAS as an organisation determined to “sustain a world leading position for the UK in Antarctic affairs” (British Antarctic Survey, 2015b), as suggested by the following excerpts drawn from interviews with academic participants:

“BAS has a very like driven culture, so a lot of people put pressure on themselves to do a really good job and to take on extra things and it’s how to manage that so that people don’t feel like they’re being a failure for not delivering things that they thought, maybe they should be able to do.” (MB5)

“There’s always been a culture—“it’s fine, I don’t mind in Antarctica working every hour that I could possibly work to get my work done, because of the unique opportunity to be there and get it done”…but when you get to half, over halfway through the year and you take your first days of holiday you start to think “I’ve just worked every day non-stop and I’m not supposed to,” and even people working weekends and things is quite normal within BAS … we work too many hours and it’s institutionally accepted at least, if not encouraged.” (MB6)

“There is obviously a need to do high level work and high-level papers and I do believe that if you want to get a permanent position at BAS you’re supposed to do one first author paper a year, on top of doing extracurricular stuff, and it just seems difficult.” (MB11)

This perspective did not only cut across all academic career stages. Non-academic participants also pointed at related issues, such as pressure (MB2: “pressure to constantly […] deliver more than anyone could deliver in a normal working day, working week, working year”), or stress (MB4: “the whole organisation is quite overstretched […] we say yes to lots of things that maybe we shouldn’t have”). The need to sustain periods of high productivity, but also other aspects of the research culture allegedly encouraged at BAS, such as the strong focus on securing grant funding and successful publication of research, both of which have far-reaching consequences in academic career progression, are not particular to this institution (e.g., Moore et al., 2017; Sabagh et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2022). Neither are the expectations, pressures, and other aspects for those pursuing non-academic functions. However, acknowledging their relevance in the reinforcement of a competitive workspace and institution can allow for a better understanding of the context where issues affecting minority employees flourish and persist, while emphasising how challenging environments like that described above can affect minorities in particular.

Moreover, the challenges and issues discussed above are rarely voiced by the participants of our interviews at their workspace, and outside the context of a study like the present one. The following excerpts illustrate why partly this may be so:

“It feels very bureaucratic, very administrative and like that they care more about their appearance and getting money than about science.” (MB1)

“For early career people and for people like on fixed term contracts is a real lack of clarity […] it would help a lot of people out if BAS would help them understand the stakes, because I experienced a tremendous amount of stress when I was kind of led to believe that I was going to be made open-ended, and then I wasn’t. It was kind of pulled back at the last minute so there was a difference between what I was told to expect and then what actually happened.” (MB3)

“People make decisions in some areas that affect other areas, but they kind of make them on their own and then they’ll implement them, and it has an impact, perhaps on my workload or […] with my colleagues, but we’re not involved in that decision making.” (MB5)

“I find it quite an authoritarian regime, like it’s very top down and … the lack of two-way communication, I think, is the main thing for me […] There’s no obvious routes for me to communicate directly with people—I would have to do it through a convoluted way that seems designed to stop you… communicating. So I kind of … I kind of … feel that they don’t really listen and that can be really frustrating at times when it’s something that’s important to you.” (MB6)

“BAS has a very sort of flat management structure, and things like that … so the number of opportunities that arise are very limited […] it’s so flat that a very small number of people have a lot of say about how things are done and you don’t often feel that you have any input. And even if you did have input that you’d often at some point think, you know, that you’re not going to be listened to, so what’s the point of saying anything?” (MB13)

Besides pointing at some of the aspects that make BAS’ structure strongly hierarchical, these narratives can be seen to reflect both the participants’ feelings of disassociation from the institution and the way their personal and professional lives and projects are shaped within this context. From the plights in securing future employment as in the case of MB3, to disillusionments towards engaging in dialogue with the upper echelons of the organisation as in the words of MB13, the issues above are not particular to BAS. They are also recurrent in many research institutions, or in many institutions, for that matter (e.g., Pilkington, 2013; Tate and Page, 2018; Ahmet, 2020) However, in a context where minorities, in particular, experience not only underrepresentation, but also discrimination, exclusion, rejection, and other injustices, on top of enduring, like their colleagues, a challenging institutional environment, a hierarchical structure could be especially damaging for them. The lack of communication, or rather the absence of actual opportunities for minorities to tell their stories and be listened to (Watts, 2008; Escobedo, 2021), adds to the epistemic injustice (Fricker, 2007), and non-existence of litigation (Lyotard, 1988), that already affect them. In this way, as our analysis suggests, BAS’ organisational culture and environment is directly involved in the demarcation and maintenance of boundaries between the minority employees and their core-group colleagues in a hierarchical way. This is because the experiences of the former in and away from the workspace do not merely differ from but are also shaped rather unfavourably vis-a-vis those of the latter.

Minority Agency, New Boundaries, and Future Hopes

Having understood, from a minority perspective, how the core group engages in internal and external identification as well as in boundary demarcation and maintenance, and how BAS’ organisational culture, environment, and structure endorses this process, we finally turn to how minority employees exercise agency, and manage boundary making. In terms of agency, minority employees often deal with the beliefs and practices they associate with the core group by finding ways to identify with it rather than by engaging in conflict. It is not uncommon for them to emphasise similarities when describing workplace relations, silently leave offences unaddressed to prioritise keeping good relations with their colleagues, and ascribe to themselves valued professional labels such as “scientist,” “researcher,” or “scholar” to articulate and materialise more democratic boundaries among them. By adopting this posture they highlight the importance and priority that being part of BAS has for their careers, while confirming at the same time the asymmetrical, and rather hierarchical, way in which this social space approaches diversity:

“I do think that a lot of the early career researchers are kind of putting forward what we think people want to see […] You dress the way someone might expect you to … um … you know you’re not wearing sport clothes around the office, you dress like a scientist should and … you have a normal scientist lunch—nothing too strange. I do not know if anyone notices it, I guess, but … if you present this image of being a good young scientist, you should be given a job in the future.” (MB1)

This is congruent with the integrationist lens adopted by the institution: The considerably tedious process that this entails for especially minority employees is not understood here as part of a power struggle where some are being silenced, transgressed even injured, and which is guided by a (Eurocentric, masculinist) taken-for-granted cultural centre. On the contrary, this is seen as a natural process in one’s inclusion into a scientific community living up to the highest academic standards. The expressed responses to the structural issues affecting minorities at BAS that the interviewees gave point at the fact that on ground agency is exercised in a way that prioritises the formation and maintenance of this rigorous scientific community (boundary) rather than challenging it. However, the interviewees did express their hope for justice during the interview process. Amongst those that were aware of the organisation’s various EDI activities, there was a general consensus that such celebrations of diversity were performative, or “tick-box measures” that were motivated primarily by self-interest:

“If we can have kind of a more diverse mix of people at that kind of management level I think that’ll help because then some of these EDI topics will then be kind of more naturally on our radar and we’ll just have a better diversity of opinions” (MB3)

“Just having a polar pride day or slapping on stonewall-certified on your application process or something like that doesn’t necessarily scream we take this seriously … it almost feels like Greenwashing but with social issues other than the environment” (MB9)

Conclusion: Calving Out a Space to Exist

“You can never say why that bias is but you do start to get a feeling that your face doesn’t fit, or your lifestyle doesn’t fit or something like that.” (MB12)

The paper concludes that, firstly BAS has indeed enriched the careers of its minority employees, and demonstrated an increased interest in EDI initiatives in recent times. However, the EDI interventions currently in place at the institution are exercised from the unmarked, dominant group’s gaze, leaving those from minorities to perform identities that they feel minimise their own true identities, marked by their difference. It is only through subduing, downplaying or concealing their markers of difference, and through self-ascription of valued professional labels such as “scientist,” “researcher,” or “scholar” do those from minorities feel a sense of belonging in the organisation, albeit partial and precarious. Besides that, the forms of rejection, discrimination, and exclusion experienced by those from minorities typically permeate in covert, subtle, and unreflective ways, rather than explicitly or through direct incidents. This, we argue, relates more to the internal identification processes shaping the dominant group in and beyond the institution, and how it approaches others from its institutionally embedded and tutored position. Given this scenario, we conclude that EDI policies at BAS, going forward, should primarily address the dominant group’s identification processes so that the organisation can increase access and participation for people from minorities in its workforce, avoid tokenistic or “tick-box” approaches to diversity management and, ultimately, transform from a space in which certain positionalities are more privileged and valued over others.

It is on this note, that we end with the reflections and advice offered by one of our participants:

“There’s some good conversations inside and I think we’ve made good progress on where we were from a few years ago. But I think now we really need to turn that into embedding it across the organisation and doing groundwork … it’s not about the big things you can shout about all the big wins in the headlines, it’s about the everyday chipping away.” (MB5)

Data Availability Statement

Excerpts from fully anonymised transcripts are available upon request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to YS5sYXdyZW5jZS4yQGJoYW0uYWMudWs=.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AL was responsible for the study conception, data collection, analysis and interpretation. LE was responsible for data analysis, interpretation and methodological development. Both authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgement is given to the participants of the MiBAS study, for sharing their stories so willingly, so openly and so courageously.

References

Ahmet, A. (2020). Who Is Worthy of a Place on These Walls? Postgraduate Students, UK Universities, and Institutional Racism. Area 52 (4), 678–686. doi:10.1111/area.12627

Bar-On, T., and Escobedo, L. (2019). FIFA Seen from a Postcolonial Perspective. Soccer Soc. 20 (1), 39–60. doi:10.1080/14660970.2016.1267632

Barth, F. (1998). Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Bentley, M., Siegert, M., Jones, A., Meredith, M., Hendry, K., Arthur, J., et al. (2021). The Future of UK Antarctic Science: Strategic Priorities, Essential Needs and Opportunities for International Leadership. Grantham Institute Discussion Paper 9. Imperial College London.

Berry, M. J., Chávez Argüelles, C., Cordis, S., Ihmoud, S., and Velásquez Estrada, E. (2017). Toward a Fugitive Anthropology: Gender, Race, and Violence in the Field. Cult. Anthropol. 32 (4), 537–565. doi:10.14506/ca32.4.05

Bhopal, K., and Henderson, H. (2019). Competing Inequalities: Gender versus Race in Higher Education Institutions in the UK. Educ. Rev. 73 (2), 153–169. doi:10.1080/00131911.2019.1642305

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic Analysis,” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Editors H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher (American Psychological Association), 2.

British Antarctic Survey (2015a). British Antarctic Survey History [Leaflet]. Available from: https://www.bas.ac.uk/data/our-data/publication/british-antarctic-survey-history-2/ (Accessed November 29, 2022).

British Antarctic Survey. (2015b). About British Antarctic Survey. Available from: https://www.bas.ac.uk/about/about-bas/ (Accessed November 29, 2022).

British Antarctic Survey. (2018). Athena SWAN Bronze Application. Available from: https://www.bas.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BAS-Athena-SWAN-bronze-renewal-British-Antarctic-Survey-April-2018.pdf (Accessed November 29, 2022).

British Antarctic Survey. (2020). The First Polar Pride [Press Release]. Available from: https://www.bas.ac.uk/media-post/the-first-polar-pride/ (Accessed November 29, 2022).

British Antarctic Treaty. (2020). Legislation. Available from: https://britishantarcticterritory.org.uk/about/legislation/#admin (Accessed November 29, 2022).

Brubaker, R., and Cooper, F. (2000). Beyond ‘Identity’. Theory Soc. 29, 1–47. doi:10.1023/a:1007068714468

Brubaker, R., Feischmidt, M., Fox, J., and Grancea, L. (2006). Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton University Press.

Butler, J. (2005). Photography, War, Outrage. Publ. Mod. Lang. Assoc. Am. 120 (3), 822–827. doi:10.1632/003081205X63886

Forthcoming Escobedo, L. (2021). “The Refractive Gaze: A Non-Roma Researcher’s Composite Perspective in Changing Times,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Change. Editors R. Baikady, S. M. Sajid, J. Przeperski, V. Nadesan, M. R. Islam, and G. Jianguo (Palgrave Macmillan).

Frater, D. (2021). Report for the first stage of the diversity in polar science initiative. Available at: https://www.bas.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/DIPSI-final-report.pdf.

Fuchs, V. (1982). Of ice and men: The story of the British Antarctic Survey, 1943-73. Anthony Nelson.

Gibbs, K. (2014). Diversity in STEM: What it Is and Why it Matters. Sci. Am., 10, 197. Available from: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/diversity-in-stem-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters/.

Griffiths, H., and Muschitiello, P. (2021). Polar Horizons 2021 Report. Available from: https://www.bas.ac.uk/data/our-data/publication/polar-horizons-2021-report/ (Accessed November 29, 2022).

Griffiths, H., Muschitiello, P., Hough, G., Logan-Park, N., Frater, D., Hendry, K., et al. (2022). Diversity in Polar Science: Promoting Inclusion through Our Daily Words and Actions. Antarct. Sci. 33 (6), 573–574. doi:10.1017/s0954102021000584

Hutchison, P. M. (2009). Breaking Boundaries: Football and Colonialism in the British Empire. Inq. Journal/Student Pulse 1 (11), 1–2.

Jenkins, R. (1983). Lads, Citizens and Ordinary Kids: Working-Class Youth Life-Styles in Belfast. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Jenkins, R. (2000). Categorization: Identity, Social Process and Epistemology. Curr. Sociol. 48 (3), 7–25. doi:10.1177/0011392100048003003

Johnson, C. P. G., and Otto, K. (2019). Better Together: A Model for Women and LGBTQ Equality in the Workplace. Front. Psychol. 10, 272. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00272

Johnson, A. (2020). Refuting “How the Other Half Lives”: I Am a Woman’s Rights. Area 52 (4), 801–805. Available from. doi:10.1111/area.12656

Kaye, K. (1982). The Mental and Social Life of Babies: How Parents Create Persons. Brighton: Harvester.

Kiss, T., and Kiss, D. (2018). “Ethnic Parallelism: Political Program and Social Reality: An Introduction,” in Unequal Accommodation of Minority Rights. Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series. Editors T. Kiss, I. Székely, T. Toró, N. Bárdi, and I. Horváth (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 227–247.

Kiss, T., Székely, I., ToróBárdi, T. N., and Horváth, I. (2018). Unequal Accommodation of Minority Rights: Hungarians in Transylvania. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kiss, T. (2018a). “Introduction: Unequal Accommodation, Ethnic Parallelism, and Increasing Marginality,” in Unequal Accommodation of Minority Rights. Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series. Editors T. Kiss, I. Székely, T. Toró, N. Bárdi, and I. Horváth (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 1–33.

Kiss, T. (2018b). “Demographic Dynamics and Ethnic Classification: An Introduction to Societal Macro-Processes,” in Unequal Accommodation of Minority Rights. Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series. Editors T. Kiss, I. Székely, T. Toró, N. Bárdi, and I. Horváth (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 383–417.

Kurzwelly, J., and Escobedo, L. (2021). “Violent Categorisation, Relative Privilege, and Migrant Experiences in a Post-apartheid City,” in Migrants, Thinkers, Storytellers: Negotiating Meaning and Making Life in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Editors J. Kurzwelly, and L. Escobedo (HSRC Press).

Lamont, M., and Molnár, V. (2002). The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 28 (1), 167–195. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107

Lamont, M., Silva, G. M., Welburn, J. S., Guetzkow, J., Mizrachi, N., Herzog, H., et al. (2016). Getting Respect: Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lawrence, A. (2022). Mud and Glee at the Crossroads: How Can We Consider Intersectionality More Holistically in Fieldwork? Area 54, 541–545. doi:10.1111/area.12826

Lee, M., Coutts, R., Fielden, J., Hutchinson, M., Lakeman, R., Mathisen, B., et al. (2022). Occupational Stress in University Academics in Australia and New Zealand. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 44 (1), 57–71. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2021.1934246

Lotman, Y. M., and Clark, W. (2005). On the Semiosphere. Sign Syst. Stud. 33 (1), 205–229. doi:10.12697/sss.2005.33.1.09

Lutz, C., and Collins, J. (1991). The Photograph as an Intersection of Gazes: The Example of National Geographic. Vis. Anthropol. Rev. 7 (1), 134–149. doi:10.1525/var.1991.7.1.134

Lyotard, F. (1988). The Differend: Phrases in Dispute. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Translated by G. van den Abbeele.

McGarry, J., O’Leary, B., and Simeon, R. (2008). “Integration or Accommodation?,” in Constitutional Design for Divided Societies: Integration or Accommodation? Editor S. Choudhry (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press), 41–88.

Mladenova, R. (2022). The ‘White’ Mask and the ‘Gypsy’ Mask in Film. Heidelberg: Heidelberg University Publishing.

Moore, S., Neylon, C., Paul Eve, M., O’Donnell, D. P., and Pattinson, D. (2017). “Excellence R Us”: University Research and the Fetishisation of Excellence. Palgrave Commun. 3, 16105. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2016.105

Mylonas, H. (2013). The Politics of Nation Building: Making Co-nationals, Refugees, and Minorities. Cambridge University Press.

National Geographic. (2018). Black and White. National Geographic. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazines/l/ri-search/ (Accessed November 29, 2022).

Office for National Statistics. (2013). 2011 Census: Key Statistics and Quick Statistics for Local Authorities in the United Kingdom. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/keystatisticsandquickstatisticsforlocalauthoritiesintheunitedkingdom/2013-10-11 (Accessed November 29, 2022).

Office for National Statistics (2021). Sexual Orientation, UK: 2019. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/people population and community/culturalidentity/sexuality/bulletins/sexualidentityuk/2019 (Accessed November 29, 2022).

Pilkington, A. (2013). The Interacting Dynamics of Institutional Racism in Higher Education. Race Ethn. Educ. 16 (2), 225–245. doi:10.1080/13613324.2011.646255

Sabagh, Z., Hall, N. C, and Saroyan, A. (2018). Antecedents, Correlates and Consequences of Faculty Burnout. Educ. Res. 60 (2), 131–156. doi:10.1080/00131881.2018.1461573

Seag, M., Badhe, R., and Choudhry, I. (2020). Intersectionality and international polar research. Polar Rec. 56, E14. doi:10.1017/S0032247419000585

Selvarajah, S., Deivanayagam, T. A., Lasco, G., Scafe, S., White, A., Zembe-Mkabile, W., et al. (2020). Categorisation and Minoritisation. BMJ Glob. Health 5, 1–3. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004508

Tate, S. A., and Page, D. (2018). Whiteliness and Institutional Racism: Hiding behind (Un)conscious Bias. Ethics Educ. 13 (1), 141–155. Available from. doi:10.1080/17449642.2018.1428718

Tzanakou, C. (2019). Unintended Consequences of Gender-Equality Plans. Nature 570, 277. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-01904-1

Wamsley, L. (2018). “National Geographic” Reckons with its Past: “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist.“ NPR. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/03/12/592982327/national-geographic-reckons-with-its-past-for-decades-our-coverage-was-racist (Accessed November 29, 2022).

Watts, M. (2008). “Narrative Research, Narrative Capital, Narrative Capability,” in Talking Truth, Confronting Power. Editors J. Satterthwaite, M. Watts, and H. Piper (New York: Peter Lang).

Waugh, L. R. (1982). Marked and Unmarked: A Choice between Unequals in Semiotic Structure. Semiotica 38 (3-4), 299–318. doi:10.1515/semi.1982.38.3-4.299

Wehrmann, D. (2016). The Polar Regions as “Barometers” in the Anthropocene: towards a New Significance of Non-state Actors in International Cooperation? Polar J. 6 (2), 379–397. doi:10.1080/2154896X.2016.1241483

Keywords: polar science, identity, diversity, equity, inclusivity

Citation: Lawrence A and Escobedo L (2023) Calving Out a Space to Exist: “Marked” Identities in Polar Science’s “Unmarked Spaces”. Earth Sci. Syst. Soc. 3:10070. doi: 10.3389/esss.2023.10070

Received: 07 December 2022; Accepted: 28 March 2023;

Published: 12 April 2023.

Edited by:

Aisha Al Suwaidi, Khalifa University, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Michael Prior-Jones, Cardiff University, United KingdomAnouk Beniest, VU Amsterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2023 Lawrence and Escobedo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anya Lawrence, YS5sYXdyZW5jZS4yQGJoYW0uYWMudWs=

Anya Lawrence

Anya Lawrence Luis Escobedo

Luis Escobedo